Over the thousand year history of Jewish life in Poland, what started out as a tolerant country became more and more anti-Semitic. There are myriad reasons for anti-Semitism in soil that is fertile for it. The Jewish people maintain themselves as a Jewish culture and community by staying together, but they have often been excluded by the community at large; Jewish culture promotes education and prosperity,but it has also sustained itself in poverty; Judaism is a religion that isn’t Christian in a Christian society or Moslem in the Islamic world. Each has fanned demonization and intolerance in its time. That a number of churches still teach that Jewish people are responsible for the death of Jesus is unhelpful and doesn’t seem “Christian” as I understand Christianity. In addition, that Jewish people are such a minority, due in no small sense to the persecution and expulsions over time and space, there are people who have never met a Jewish person and believe whatever they are educated to believe. Now the Moslem world is demonizing Jewish people to delegitimize the State of Israel: a home yearned for for thousands of years, inhabited by remnants of Jewish community throughout time, and needed for refuge from countries which were believed to be home.

So the story of my Abba and Ema took place in the anti-Semitic soil of Czestochowa, Poland. Jewish culture and family life was rich and diverse enough, however, to weather the anti-Semitism around them. While Walter’s father, Herbert, left Germany in 1937 to work and bring as many of his family out of Germany as he could, my mother and father, not married until after the war, were living in an increasingly anti-Semitic Poland, an anti-Semitism fueled further by the culture of Nazism across its border.

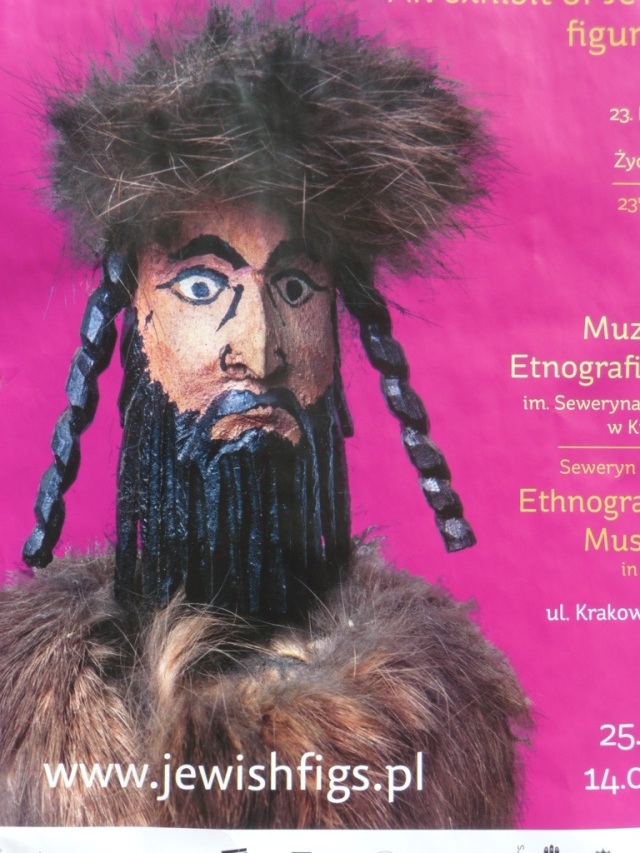

My father, Israel Hoffer, talked of seeing Orthodox men stopped in the street to be taunted by thugs. He described an incident in which he witnessed thugs cutting off the beard of a religious man. Just witnessing this was humiliating for my Abba. Can I tell you for certain if this was before 1939 or after? No. However, the accumulation of stories deems this unnecessary.

My father worked in the family grocery store on Novarynek and Warschawska Street. He was born in 1909, so he was 30 when the Nazis occupied Poland. He was married. I don’t know his wife’s name or anything else about her except that she did not survive the Holocaust. She died in Bergen Belzen. I hope someone remembers her and that her memory is a blessing.

His family was orthodox and Chasidic. His father, David, wore the traditional orthodox garb of his sect, which I believe was Gerer because that is the sect whose music my father most loved. However, I never saw my Abba in anything but the contemporary style of the day in photographs taken even before the war. Was there a tension between him and his father around the integration of religion and tradition? I’m guessing, yes.

My father loved to read and study. His interests were deeper and wider than his upbringing would allow. He also was a self- professed smart alec in school. This was not handled well in his family, so his cheder, school, education ended in the eighth grade. He continued his education as a self-educated man. He loved to study Talmud and talked to everyone he could at every opportunity. For the rest of his life, he would read the daily newspaper(s) cover to cover every day.

He had two sisters. The older sister, Sarah, immigrated to Israel with her husband, Michael Weisz. There they had two sons, Tsvi and David who, to this day, are living in Israel with their families. His younger sister, Bashka, had also immigrated to Israel with her husband, whose name I never knew; however, she did not acclimate to the life in Israel and with her husband, she returned to Poland. They did not survive.

My Abba, Ema and both of their large families were among over 35,000 Jewish people in Czestochowa.

How did my Abba manage? What happened to their family grocery? What random acts of terror did he experience and witness? How and when were his parents, Rochma and David, murdered? His sister and brother-in-law? In September of 1939, when the Nazis went from house to house, banged on every door and hounded out the men with hollering and beatings and rooted them out of their residences into the streets, parks, fields and churches, did my paternal grandfather make it back home after the random shootings? My father did, but what had he experienced? My maternal grandfather, Abraham, and Uncle Daniel did? What of my other grandfather, David? Great-uncles? Cousins?

My Ema’s father was badly beaten, but returned home. My Ema’s brother took a longer time to come home. This was when my Ema, her mother, Bluma, and sister, Mania went looking for him. This was when my Mom encountered a strangely cruel young German who made her look through a pile of dead horses and people to see if her brother was there.

Around 300 men were murdered randomly, and approximately 3000 others, Jewish and Polish men, disappeared. How many of my large family? How does one proceed in this climate of random terror?

They tried to normalize. I understand, through the memoir of Jerzy Einhorn, a survivor of that city, that in Czestochowa, the Judenrat, a group of Jewish leaders, was organized by the Nazis into an intermediary group between the Nazis and the Jews. Jerzy Einhorn said that they were a respected group of people who acted with integrity. What did my father think of these people? They were in an impossible position and suffered the same fate as everyone.

In order to get food, everyone had to register. So the Nazis knew every man, woman and child. Everyone who was of working age had to get a worker’s permit. People were led to believe that a worker’s permit lent them security and that laborers were needed for the war effort. People surmised that if they were necessary, they had a chance of surviving.

My mother and Mr. Einhorn both talked about how people tried to live as normally as possible. Tradition was maintained. People socialized. Fear was kept in check. Already a survival mentality had set in.

In December of 1939, Christmas Day, another Jewish pogrom broke out. Poles were ordered by the Nazis to loot and burn. A major synagogue was burnt to the ground. Houndings, “razzias” happened at random; however, the Jewish holidays were especially scary. Nazis studied the Jewish calendar quite carefully, and even in timing, they were sadistic. Did my Abba continue going to shul?

No school, no cinema or concerts, and curfews restricted Jewish lives; however, people continued socializing. White armbands with the blue Star of David were decreed. Non -compliance meant death. Some men, 15 and over, disappeared. It was believed that they were taken to forced labour. Having a work permit, a red double folded piece of cardboard, and a place to work was thought to provide some security. Was my Abba still working in the grocery? Had the Germans appropriated their and my Ema’s family’s businesses yet?

1940 passed this way. In April, 1941, a new decree defining the boundaries within which Jewish people had to live was established. It came to be known as the “Large Ghetto”. My Ema’s family at 37 Warshawska St. could stay in their apartment, but they had to share it with two families who had to move from residences outside these boundaries.

Could my father and his wife stay in their apartment? Did they have to move? Were the other men in their family still alive?

What could people take with them? Which of their possessions was plundered or sent to the Reich? Jewish people were into survival, so who can we say is materialistic?

At this time, people from other communities, shtetls or villages,were forced to move. 20,000 more Jewish people needed living quarters in Czestochowa. Who did my Abba and his wife live with? Did they give their possessions to non-Jewish friends or associations for safekeeping? Were they able to put anything away for the future? An edict requiring the surrendering of all furs is an example of how the Reich systematically collected all things of value. From that point on, a Jewish person found with a fur to keep them warm during the bitter winter would be killed.

A few months later, in August of 1941, the overcrowded Jewish ghetto was hermetically sealed off from the rest of Czestochowa. Jewish populations experienced this in cities throughout Poland. On that day, someone tried to leave and he was shot by Senior Constable Handtke, a trigger happy Nazi, and allowed to die slowly. Examples like this were made throughout Poland.

Groups of Jews were taken out for forced labor to places outside the ghetto. What forced labor did my father do? Did he meet Polish workers who could give him some news? Could he sell anything to take care of his family? When did the realization of the well planned trap that the Nazis were setting become apparent? How did the family support each other? What hopes did my Abba hang on to?

My Ema spoke of “managing” as long as her family was still intact, and it was.

By May of 1942, rumors of mass murders persisted. Intellectuals and activists were taken away and not heard from again. In June of 1942, the infamous Captain Degenhardt issued an order for an Appell, a roll call of all Jews between the ages of 15 and 50, men and women. This took place peaceably, but proved to be a dress-rehearsal for the next phase of a detailed and well thought-out plan for the mass extermination of our people.

Around the High Holidays, 1942, the Ukrainians,chosen or trained for their brutality, were brought in, and workers returning from their shifts reported seeing around a hundred “cattle cars” lined up at the train station. Panic set in, but alas what to do with it? The group that tried to escape was shot. Everyone living on Kawia, Koszarowa, Garibaldi, Wilsona, and Warszwaska Street where my family lived was called to report with their work permits, which everyone knew by now was a ruse. They dressed in their best and packed what valuables they had left.

The first selection for deportation was the day after Yom Kippur, 1942. That was the day, my maternal grandfather, Abraham Gruen, “zichrono l’vracha; May his memory be a blessing”, was deported to Treblinka, forever lost to his family.

Were other relatives on that transport? My Ema’s mother decided to take my Ema, Sala, and Dodah (Aunt) Mania into hiding in an attic. They were there for five weeks and nearly starved before they surreptitiously joined a group of remaining Czestochowans moving to a smaller ghetto in the poorest part of the city. There they reunited with their son and brother, Daniel, called Dadek.

I wish I could ask my Abba what happened to his family at that time. The evacuation to the death chambers of Treblinka went on for three weeks. Of 8000 people gathered that day, September 22, 1942, Degenhardt selected 7000 to the right to load 100 people in each of 70 cattle wagons, 340 to the left and the rest of the people he had shot on the spot. Any anguished resisters were murdered. The 340 were ordered to take our dead and bury them in a mass grave.

At the Topography of Terror, a museum in Berlin, Walter, Ralph, Alice, Jessica, Zach and I saw photographs of the German Nazi bureaucrats,“desk perpetrators”. Nothing in their demeanors revealed the sadism so evident in the results of their machinations. These were professional, but banal men who might have done truly wonderful things if they had not allowed their talents to be subverted by a sadistic leader and system. On January 20, 1942, at a luxury villa by the beautiful Lake Wannsee outside Berlin, the plan to slaughter human beings with industrial efficiency was agreed upon. Only the details needed to be worked out there, for these individuals had brought their part of the plan to the table.

The last of these deportations to Treblinka took place on October 4th, 1942. In between deportations, the German patrols with specially trained police dogs went looking for Jewish people who tried to hide in cellars, attics or “bunkers” some managed to construct. The German patrols barricaded off the searched areas and cut supplies of water, electricity, and gas. They lured the starving out with promises of food. They tortured people they caught for information about other hiding places. Fortunately my Mom, her mother and sister were able to come out of hiding when they could blend in with people going off to the small ghetto where the remnant of the Jewish Community was taken.

Most of the Judenrat and Jewish police were included in the mass deportation. Of the 56,000 people, around 5,200 Jewish people were left in Czestochowa. Among them, my Abba, Israel Hoffer, my grandmother, Bluma Gruen, my Ema, Sala Gruen, my Dodah Mania and my Dod Daniel. They were prisoners and slave laborers.

After the deportations and clearing out of the Large Ghetto of its inhabitants, the Nazis moved the survivors to the small ghetto. My maternal Savta worked in the makeshift hospital in the small ghetto. My Ema, Savta, Dodah and Dod were taken to work at Hasag, an acronym for the German firm, Hans Schneider Fabriken A.G.

My Abba once told me that he had a job clearing up the belongings left behind in the Large Ghetto. I believe that he must have been one of the men selected to live in the house on Garibaldi Street, for after the Ghetto had been searched, a crew of over 50 men were sent to work. The job was to collect “all men’s clothing into one hall, men’s underclothes into another, then women’s clothes, women’s underclothes, better furniture and lamps, sewing-machines and electrical goods, pictures and sculptures, precious metals such as silver and gold – all neatly sorted.” (Einhorn, The Maple Tree Behind The Barbed Wire: A Story of survival from the Czestochowa Ghetto; 1996) He told me that one of his guilty pleasures was taking some books he found so he could read in his room.

Day and night work shifts at work sites in and out of the ghetto were twelve hours, and if no additional food could be conjured up, a piece of bread to last the day, weak coffee and a dab of jam was the diet with watery potato/turnip soup at the end of the shift. Eventually many died of starvation.

The small ghetto was surrounded by a man-high barbed wire fence twisted between large posts. The area around was totally evacuated and was constantly guarded by heavily armed soldiers patrolling day and night in the streets beyond the barbed wire. People who tried to escape were shot if caught and left for others to see.

My Ema talked of an escape she made to a farm outside the ghetto. While the details are not so clear in her Spielberg Testimony, what is clear is that a sum was paid, she and a few others were hidden in a barn for the night, and the next morning the woman whose farm it was came to tell them that something was terribly wrong. The “chickens crowed instead of the roosters” or some such malarkey. They understood they had to leave. My mother describes a long treacherous walk back to the small ghetto. Dogs and soldiers patrolling the woods were a constant threat. They (who?) made it back to the ghetto. While the details are blurry, this event is corroborated by other such stories of people betrayed with no place to go, but to return to the ghetto.

The next event I’ve learned about occurred on a morning in January, 1943. Day and night shifts were called to line up for an Appell (roll call). Resisters were killed and German police reinforcements were sent. The sums recorded were that 350 Jewish captives were sent to Radomsko where an Extermination Aktion was occurring. They were sent to Treblinka. 200 others were killed in the square where the Appell took place or shot at the Jewish cemetery which had become a place for executions and mass burials. My mother, her mother, sister, and brother were still alive. My father was alive.

Resistance, although seemingly fruitless and provoking what seemed like worsening circumstances, was reported as raising hope and the morale of the prisoners.

The liquidation of the small ghetto started on June 26, 1943. With extra German manpower and surrounded by extra munitions, all Jewish people were called for Appell. People were chosen at random and not so randomly, taken to the cemetery, stripped and shot. Jerzy Einhorn described the spirit of the prisoners. They sang HaTikva and implored the others not to forget them as they were being loaded on the so familiar trucks. The liquidation of the Czestochowa ghetto was on the orders of ex-lawyer, Hans Franck, that all Jewish ghettos were to be liquidated. If any Jews were left, they were to be in prison camps.

“On June 28, German cars drive around the ghetto, and over loudspeakers offer jam, hot soup and amnesty to anyone still remaining hidden. They are given until June 30th – two days to report at the exit of the ghetto.” There was another mass grave in the cemetery for those who came out of hiding. The small ghetto was then dynamited. Only ruins of the buildings remained.

My Savta Bluma, “zichrona l’vracha”, did not survive this Aktion. My Ema , Dodah Mania, and Dod Dadek were apparently kept at Hasag during a day shift, and their mother did not come to the night shift as some others had. They could only assume that she chose to hide as she had done when the Large Ghetto was being liquidated. Walter, I, Jessica, Ralph and Alice said Kaddish at the Jewish Cemetery when we were in Czestochowa on Friday, June 28, 2013, 70 years to the day.

My Abba was also in Hasag, as was my Mom’s best friend, Hala Lastman and her future husband, Joseph (Yuzek) Soski.

When the surviving inmates were taken to Hasag, nothing was ready for them. For three days, my Ema talked of sleeping on the hard ground outside. After three days, they were assigned to their huts. They worked in two shifts, from 7 to 7, two weeks in the daytime and two at night. Most prisoners worked seven days a week with a few free on some Sundays. Jerzy Einhorn wrote about the routine. “Work after the Appell begins on an empty stomach. At nine o’clock, morning or evening, we have a fifteen-minute break for breakfast – a large mug of more or less hot surrogate coffee made of chicory and a hundred grams of black bread. At exactly twelve o”clock- day or night – we have a thirty-minute dinner break. Then we are given a large bowl of hot soup made of turnips and Swedes. What one is given in an aluminum bowl depends on how far down the ladle goes – the deeper the more there is to eat, the shallower, the more watery the soup….At the end of the work stint, for the second time every twenty-four hours – evening or morning –we are given a mug of chicory coffee and 100 grams of black bread. ”

Every survivor talked of the prevailing hunger. While some could manage, others became “muzelmans”, prisoners who owing to malnutrition became totally apathetic. “The name comes from a related work in Yiddish – a miser man – and has nothing to do with Muslim (Einhorn).” These people did not live much longer.

I’m not sure what my Abba’s work was, but I know that my Ema worked with ovens……something to do with the bullet shells to be sent to the front. She used these ovens to bake extra bread whenever a Polish worker who came to work and could leave at the end of the shift brought flour. This was risky, but as my Ema said, “I’m still here.”

In the meanwhile, selections were still being made for execution and burial in the Jewish cemetery. Anyone left of the Judenrat and the Jewish police was murdered by the end of July, 1943. Einhorn praised the Jewish Administration for their comportment throughout the brutality of that time and was grateful for their help in maintaining dignity and faith in human beings. He also described a solidarity between the prisoners. The brutality of Degenhardt and his underling Onkelbach was mitigated by a Director Luth (umlaut over the u). He had them transferred, and there was a better atmosphere for a time.

In late winter of 1944, a typhus epidemic broke out in the camp. My Abba was one who fell ill. The Germans threatened camp liquidation if the epidemic was not quickly contained. It is surmised that the Germans helped contain the epidemic because their job in the camp kept them away from the front where they had by now lost, but had not surrendered “unconditionally”. “Every item in the camp was deloused. Every hut is closed off and the vermin all are smoked out in 36 hours, all doors and windows effectively sealed.” (Einhorn) My Abba recuperated while many did not.

Much of the work sent out by Hasag was returned as deficient. My Ema spoke of “resistance”. More prisoners were brought in from Lodz. These prisoners were plied with questions. My Abba told me once about acquiring a piece of newspaper with an article about the advancement of the Allies. Another inmate who my father considered a friend asked him for the paper so that he could roll some tobacco for a cigarette. My Abba told him that he needed to keep the article to help maintain hope. This inmate never spoke to him again.

With the newly arrived prisoners came some brutal guards. They believed they could do anything with impunity. A guard, Dzieran, for example, selected victims to amuse himself and his dog. Captain Bartenschlager shot women in the forest. On one occasion, Captain Bartenschlager brought twenty of his guards to wake the night shift two hours into their sleeping time, herded them off to the station with blows from sticks to unload the new guards’ heavy luggage. Director Luth had them transferred from Hasag immediately.

Despite some kindnesses, many succumbed to the cold and malnutrition, became apathetic and hopeless and died.

In the middle of January, 1945, the Germans packed everything they wanted to take with them and it was a lot . The Russians were close. Prisoners had to help. Prisoners were pushed to their limits and worked for fifteen hours a day. It was clear that the camp was to be evacuated.

January 15, 1945, a long train of cattle cars familiar for transporting humans came. On January 15, the Germans squashed 3000 prisoners into it. On January 16, 3000 more were sent away. On January 15 or 16, just one or two days before the Russians liberated the camp, my Abba, Uncle Dadek and Joseph Soski were on the transport. They were sent to Buchenwald. My Abba was there, then, January 30, at a camp Laura, then the death march. That’s what I know. He, #114372, survived. Joseph survived. Uncle Daniel did not, and we don’t know what happened. Zichrono L’vracha; May his memory be a blessing.

Only a few hundred of the over 6000 prisoners on these two transports survived.

Hasag was liberated by the Russians on January 17, 1945. More descriptively, the Germans were gone.

My Mom, now 20 years old and her sister, now 18 walked out of the camp wondering where to go. My Ema talked about how unfriendly people were to them as they walked down the street. She remembered the comments stated like questions, “You survived?” Only one acquaintance of her parents asked if they had a place to spend the night. He gave them a room. The following day, she knocked on the door of the apartment her family was forced to leave, and a woman opened the door. In the entry way was a large figure of Jesus on the Cross. My Ema couldn’t speak and left. She went to one of the people who her parents had given some possessions for safekeeping. They said that they didn’t have those things anymore. She asked for money for a pair of shoes. I think she got that. I don’t remember, but I hope so.

She couldn’t wait to leave Poland. She worked as a baker for the Russians for a few months. The war did not end on the American front until May, 1945 and on the Asian front, August, 1945. When she could, my Ema smuggled with friends to the American Zone and settled in Feldafing in a Displaced Persons Camp. There she found her cousin, my Abba. I don’t know how he arrived in Feldafing. He courted her with poetry that he wrote. They married and resumed their lives, each navigating their way through their losses and memories. They arrived in New York in October of 1947. Born on February 28, 1948, I was named after my grandmothers, Rochma and Bluma; Ruth Flora. Four years later, my brother was born and named after his grandfathers, Abraham and David; David A. Hoffer.

For more about Ema’s story, see Ema’s Spielberg Testimony and Mom’s Life Before the War